How Victoria Lemos Would Fix Atlanta

How I’d Fix Atlanta — Hire An Official City Historian

Victoria Lemos

As my friend King Williams likes to say, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it sure does rhyme.” From potholes to prison conditions, Atlanta has had the same issues since it was born almost two centuries ago. As I’ve spent the last decade diving into the city’s history, it’s always confused me how ATL’s issues remain so similar. Why can’t we solve things? Or, at the very least, why can’t we come up with better solutions?

[Editor’s note: LOL, truly. Welcome to How I’d Fix Atlanta, everybody.]

In its 188-year history, the City of Atlanta has only ever had one official historian—a white man named Franklin Miller Garrett. He was born September 26, 1906, in Milwaukee, WI and moved to Atlanta in 1914, after his father accepted a job here. Eight-year-old Franklin wandered around outside their hotel off Peachtree Street, and he was in awe of what he saw.

After graduating high school in 1924, he began his first job as a Western Union delivery man out of downtown Atlanta, and would do this job for 14 years. Exploring the city this way definitely led to his future as the city’s historian. Over his long career, he created a necrology of all the dead white men within a 30-mile radius of Atlanta, spent 28 years at the Coca Cola Company (later as their historian), published Atlanta and its Environs: A Chronicle of its People and Events in 1954 (which cataloged events—mostly those featuring white men, it should be noted—from 1821-1939), and was officially named Atlanta’s historian in 1974.

Garrett’s impact on Atlanta’s history lovers cannot be overstated. I relate to him in many ways. I’m an outsider, a dreaded northerner, white, insatiably curious, and I’ve spent countless hours wandering around the city developing a passion to document and share Atlanta’s history with others.

In my decade of being a tour guide and my last six and a half years producing an Atlanta history podcast, I’ve noticed some recurring themes. They can largely all be described as “same shit, different year.” I have to remind myself that not everyone knows the city’s history—it’s not even taught in our schools! City Council recognized this and passed an initiative in 2023 that encouraged APS to work with the State of Georgia to implement an “Atlanta History” class to the curriculum. As our current political regime is making it harder to research and share history, I think ATL, once again, needs an official city historian on staff.

The beauty of Atlanta is that we’re still trying to figure out who we are. Other U.S. cities have strong identities linked to iconic geography, built environment, history, or bodies of water, but Atlanta’s only DNA is marketing.

Put another way: only two U.S. cities with populations of more than 300,000 are located on a non-navigable waterway—Atlanta and Denver. Denver had the gold rush and Atlanta had speculation. When the State of Georgia decided to build a railroad to connect to the midwest in 1836, rail workers and land speculators made their way to Terminus, establishing a small settlement. Atlanta was officially named in 1845 and grew steadily until July of 1864, when the Battle of Atlanta sealed the fate of the Confederacy and marked the coming end of the Civil War.

ATL was in shambles at the time, but earning its Resurgens motto (Latin for “rising again”), city leaders, businessmen, and the Chamber of Commerce set out to promote the Gate City as the place for all your business needs. In 1871 they were mailing out a “Guide to Atlanta” for people and companies inquiring about this New South city and, by 1903, 15,000 handbooks had been sent around the country. In 1916, the Chamber began publishing the City Builder, which further touted its capitalist triumphs. The city’s population rose and rose. Today, it sits at just more than half a million people.

Atlanta’s marketing is always looking toward the future. We love a new development, a new stadium, new corporate headquarters, etc. But we almost always forget—purposefully or not—that things have happened over the last 188 years that have gotten us where we are, in both good and bad ways. I believe that looking to the past can help us innovate as we come up with ideas to solve current issues, especially since we’ve had many of these issues since 1837.

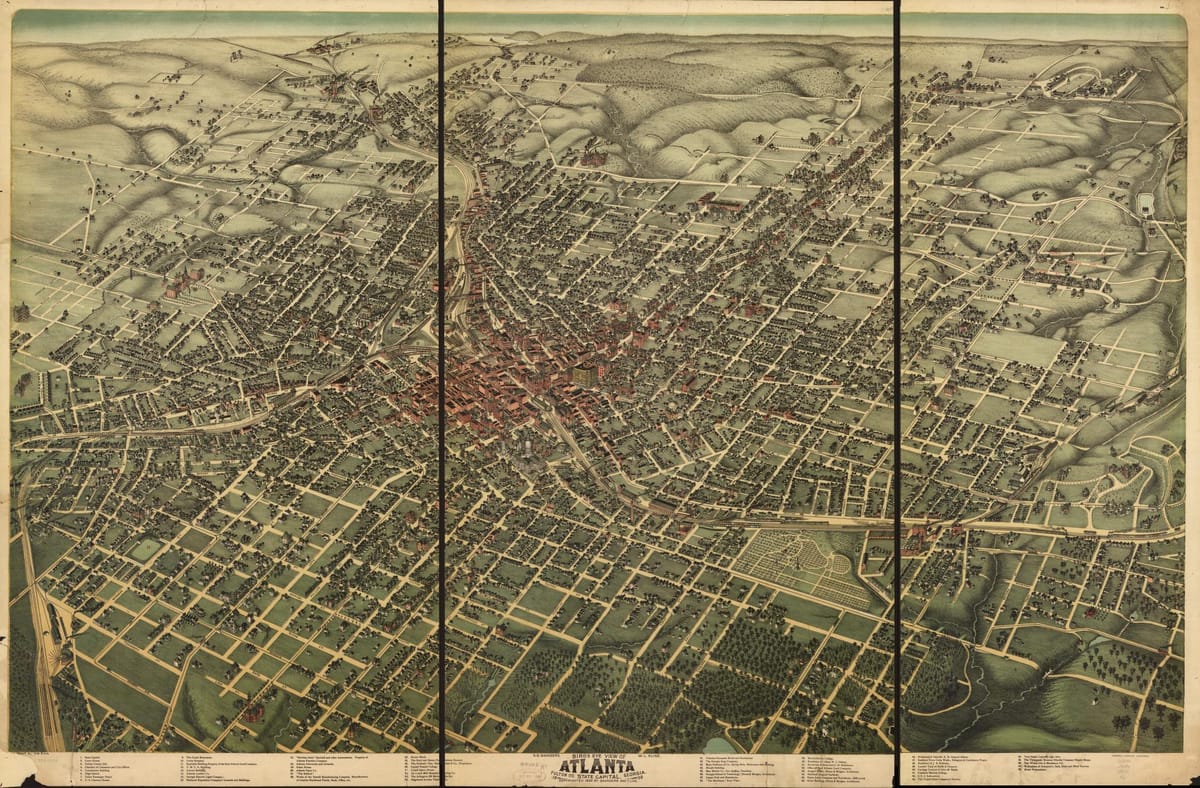

When a water main bursts or a sinkhole appears on Ponce de Leon Avenue, an official city historian could analyze the 1892 bird’s eye aerial map, revealing old topographies and neighborhood creeks. Pinpointing locations on this map may show a creek running under the street or significant changes in topography over the past century.

When MARTA crews hit unforeseen streetcar tracks that delay the BRT project (twice!), the city historian could explain the robust trolley network that Atlanta once had, starting all the way back in 1871 with mule-drawn cars that went out to the West End. When Joel Hurt installed the first electric line in 1889, the system grew exponentially across the city.

When the city debates making Streets Alive permanent, the city historian would be able to highlight that our parades and festivals are what makes Atlanta so special. The first lantern parade was put on during the 1887 Piedmont Exposition in Piedmont Park, with more than 200 riders on penny farthing bicycles. A bar extended from the hand piece and curved backward, so as to rest on the small wheel of the bicycle that was dressed with anywhere from six to 20 different lanterns. It was our cyclists in 1896 that pushed for the city to close Peachtree Street for a set time each day, removing cars and wagons and leaving it open to cyclists. That was actually the first Streets Alive!

When city leaders struggle with NIMBY opposition to zoning reform, the city’s historian could point out that we were the second U.S. city to enact racialized zoning. Atlanta’s first attempt was in 1916, led by Councilman Claude L. Ashley. After several knockdowns from state and federal courts, they removed the racially explicit language and replaced it with economic exclusion as a proxy for racial exclusion. This 1929 zoning code was the first not to be overturned by the courts and it’s the same one we’re using today. Maybe it’s time for a change.

When the city cracks down on Cop City protestors, the official Atlanta historian could remind everyone that civic resistance is not new. In the 1930s, as labor-movement Communism took hold, especially with Southern Black Americans, the city attempted to crush the movement and suppress activists in any way possible. The stories of the “Atlanta Six” and Angelo Herndon reflect the ongoing battle against dissent, baseless charges, the “Atlanta Way” by all means necessary, and the tragic conditions of the Fulton County Jail. Any of these fights sound familiar?

The City of Atlanta historian could gently nudge city leaders with the fact that we’ve been reimbursing citizens for pothole damage since the very beginning. In 1881, George McKinney received $16 after his carriage was damaged by a pothole on Forsyth Street.

By reinstating our city historian, Atlanta could better understand its past, engage meaningfully with its present, and approach future challenges with a more informed perspective. As much as Garrett’s work laid the foundation for documenting our city’s history, it also left out groups of people that meaningfully shaped ATL’s identity.

The history of Atlanta is complicated—it’s up to us to reframe it, dig deeper, and listen to voices that were never amplified. In doing so, we might finally be able to achieve real progress.

Victoria Lemos is an amateur historian and local tour guide who produces a history podcast called Archive Atlanta. Her goal is to share ATL’s history with as many people as possible, because it's harder to care about something you don't understand.

How I'd Fix Atlanta is an essay series by ATLiens for ATL. In each of these pieces, a thoughtful human argues for one way we could make our city better. Sometimes the ideas are serious. Other times? A little more lighthearted. From infrastructure to food trucks, public transit to wildflowers, nothing is off limits.

How I’d Fix Atlanta was created by Austin L. Ray. It's a free newsletter sent on a Thursday of most months. It's also an annual zine that costs money. Sometimes it’s a performance on a stage. Other times, it’s a fundraiser. It's always a bunch of stickers. Occasionally it's featured on a podcast or a legendary WABE show. How I’d Fix Atlanta is large, it contains multitudes.

Each writer is paid $800 for their essay. Wanna help support the series? Reply to this email to learn more about sponsorship opportunities.