How Spencer Hall Would Fix Atlanta

How I’d Fix Atlanta — Rebrand The Braves Now

Spencer Hall

In a town rife with decades of Sport Disappointment, only one franchise can honestly say it's delivered on the promise of generating actual happiness: The Atlanta Braves. The bar may be low—who wouldn’t look like overachievers compared to the Falcons and the Hawks?—but the point still stands. For reliable sports happiness, the city’s baseball team—the holders of actual, verifiable, repeated championships—presents the most dependable oasis in this quarter of the sports desert.

All the more reason, then, that they should change the name of the team, immediately and forever. There are several great cases for changing the name, of course. (Including one easy option that would honor Hank Aaron.) For anyone interested in the most moral thing to do, changing the moniker of a professional sports franchise somehow still named after Native American iconography in this unholy year of 2025 would obviously be the right thing to do. A predominantly white crowd doing the Tomahawk Chop in a state where Andrew Jackson’s ethnic cleansing of the Cherokee and Muscogee (among others) took place should be obvious enough to stop, but evidently it’s not.

But that’s nagging you, right, asking someone to know what any of that means? That’s too much to ask of an average or mediocre person. Looking at this bell curve and the long arc of history, that’s most people. No one’s ever gotten anything done by expecting the right thing to just happen, or expecting average people to do the right thing.

Instead, I’m going to lean on the one angle I think might actually convince the most people in the quickest fashion. The Braves as a team continue to present the most reliable sports joy in the city of Atlanta.

The Braves as a brand, however, are cringe.

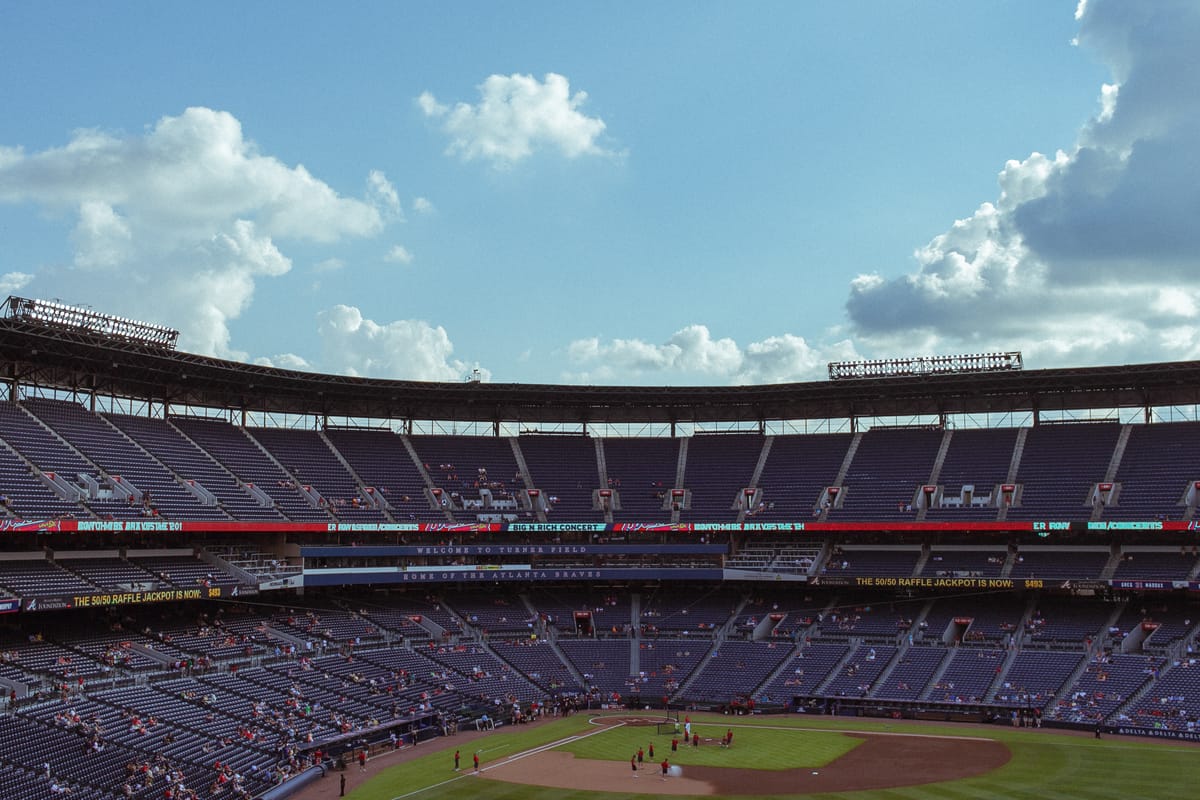

They’re soooooo cringe. Cringe AF. And to be perfectly honest with you, they’ve always been cringe. I possess only the deepest bonafides in the history of the Atlanta Braves being deeply and irrevocably cringe. The first sporting event I ever attended was an Atlanta Braves game at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, a concrete multipurpose bunker half-covered in garbage bags hosting the Braves from 1966 to 1996.

At that first game I ever saw, the team was awful. Its best player was Dale Murphy, a saint who deserved so much better than the half-empty frying pan of sunblasted concrete strewn with the unemployed dregs of weekday drunk ATLiens as an audience. At the time, the Braves maintained a little tipi out in left field for the team’s mascot, Chief Noc-A-Homa. When the Braves scored, he came out and danced.

I was in elementary school and thought this was absolutely bonkers, mostly because I thought he lived out there all the time, and that Fulton County Stadium presented a pretty crap residence for someone as a 24/7/365 arrangement. Later, I’d realize it was also embarrassing, particularly after someone underlined the essential pathos of Chief Noc-A-Homa by hitting him in the head with a thrown object during a game and knocking him out cold.

The Braves started cringe, and folks, they stayed cringe. They lost a zillion games a year for decades straight. Their other star player, Bob Horner, looked like the kid from Bad Santa, and squandered at least some of his potential when he contracted a terminal case of what Lewis Grizzard called “Heinekenitis.” That’s right, in the 1980s, a sports columnist could openly call you a beer drunk in the paper without getting sued into oblivion. This, to me, defines true freedom of the press.

The Braves lost Chief Noc-A-Homa to a contract dispute in 1986, but kept the logo and the name through their transition to Turner Field. Cringe continued even during the winning years, since the Braves followed the most cliché Atlanta story arc possible: Moving from their original, kinda-crappy apartment downtown into one with exposed brick walls, then eventually moving to a fancy new build OTP when maturity and the real money arrived.

That new stadium sits just a short car ride from my house. I haven’t been there, and I’m never going there. This isn’t just because I object to the mascot, though I certainly do. I don’t go because a) I’m not a baseball fan and b) because the Braves are just a little embarrassing at all times. I embarrass myself on a daily basis without needing an expensive supplemental form of shame, thankyouverymuch.

Sitting in a stadium with 40,000 people doing the Tomahawk Chop in a new urbanist pop-up shop plunked right off 285 is cringe. Watching Cody and his dad from Cumming run across Northside Parkway after parking their F-950 in a Honeybaked Ham store’s parking lot—where it will be booted—to go do the Tomahawk Chop is cringe. Calling all this racist garbage a “tradition” is also cringe, especially since the Chop only dates back to 1991.

Cringe is the Braves confirming every truth about Atlanta I don’t want to acknowledge. I want to be able to say this city is evolving into a place with all the fittings of a proper city, the kind they have in literally every other goddamn country in the world. I want to point out neighborhoods in which you can walk around (there are a few!), restaurants and places to hang out that aren’t desiccated office parks in disguise (they do exist!), and the city’s multicultural fabric that makes it better, more resilient, and more robust than other Southern cities that failed to take the on-ramp to the 21st century.

But you absolutely cannot do that at a Braves game. They play in a parking lot of a parking lot just north of a half-dead mall in an anti-neighborhood with all the character and pulse of a recently deceased corporate laptop. Can you ride a train to any of it? Of course you can’t.

Perhaps most cringe of all? The team is owned by a publicly traded company and the move to Cobb County was the work of Liberty Media, which is controlled by a Trump-loving billionaire who is the largest American land owner 10 years running and who lives in Colorado.

There is no escaping so many of the allegations I’d like to dodge about Atlanta. The Braves suggest that our city might exist solely as a legal pass-through for corporate money. The Braves suggest we might just be a parking lot attraction devoid of community, character, or soul. The Braves suggest there might not be an actual Atlanta—just a series of money traps planted in between tiered real estate solutions intentionally disconnected from each other and the idea of ever having a city where people know each other and gain an ounce of communal connection.

And even after that long list of allegations, there are still a bunch of people in the South playing Native American dress-up like the clueless rednecks I tell everyone they’re not. Help me lie to others and myself about you, my neighbors. Help me tell one truth about all the nice things I’d like to believe about this city. We can start by ditching the goddamn name. The rest is already cringe enough all by itself.

Spencer Hall writes the Channel 6 newsletter with Holly Anderson and is a co-host of the Shutdown Fullcast podcast. He has lived in Atlanta for a quarter century and loves the city very much despite its five million problems.

How I'd Fix Atlanta is an essay series by ATLiens for ATL. In each of these pieces, a thoughtful human argues for one way we could make our city better. Sometimes the ideas are serious. Other times? A little more lighthearted. From infrastructure to food trucks, public transit to wildflowers, nothing is off limits.

How I’d Fix Atlanta was created by Austin L. Ray. It's a free newsletter sent on a Thursday of most months. It's also an annual zine that costs money. Sometimes it’s a performance on a stage. Other times, it’s a fundraiser. It's always a bunch of stickers. Occasionally it's featured on a podcast or a legendary WABE show. How I’d Fix Atlanta is large, it contains multitudes.

Each writer is paid $800 for their essay. Wanna help support the series? Reply to this email to learn more about sponsorship opportunities.